This isn’t a list of reviews, or even plot summaries. It’s a collection of notes, reactions, citations (a minuscule fraction of the seemingly innumerable I’ve underlined, tabbed or copied into my journal this past month) and experiences I had while reading.

I’ve been contemplating making this a weekly or fortnightly round-up.

Sontag: Her Life and Work, Benjamin Moser (2019)

I started this massive tome in 2021, reading about half of it. I started it up again at the end of January, about one third in. I confess I was drawn back in because of cancer, which feels somehow a little banal and a little voyeuristic, and also very natural. Moser's last two sentences sum up the project of his biography:

Aristotle had written that "metaphor consists in giving the thing a name that belongs to something else"; and Sontag showed how metaphor formed, and then deformed, the self; how language could console, and how it could destroy; how representation could comfort while also being obscene; why even a great interpreter ought to be against interpretation. And she warned against the mystifications of photographs and portraits: including those of biographers.

What a complicated, painful thing to perceive and be perceived.

I have difficult relationship to Moser, public figure, who looms large over the English-language versions of my beloved Clarice Lispector, and who is by many accounts at best a bully and potentially academically dishonest. And yet, I was caught up in this biography, because it’s hard not to be caught up in Sontag. (I’m amused to note that Johanna Hedva, who comes up later in this book list, considers that he “writes like a twerp.”)

There's Always This Year: On Basketball and Ascension, Hanif Abdurraqib (2024)

I wrote and thought much about this text, overwhelmed by the thought that I could excerpt always more, because the language is beautiful (ditto for Morrison, which I read in tandem). The thing to which I return over and over is performance: as in excellence chronicled by Abdurraqib, as in performing the rites of community, as in the poetic act of telling.

“I propose that the difference between being naked and being bare is that in a state of nakedness, the end can be seen even if it hasn't arrived yet. It has less to do with what one is or isn't wearing or showing, and more to do with how poorly one keeps the inevitable hidden or how long a person can hold back the undoing (pleasureful or less so) that awaits them.”

Paradise, Toni Morrison (1997)

A book I started when I first decided I would read all of Morrison's novels in 2022 and never finished, because of its violence and narrative density. I'm glad I finally returned to it this month and wrote about it. “How exquisitely human was the wish for permanent happiness, and how thin human imagination became trying to achieve it.”

Small Bodies of Water, Nina Mingya Powles (2021)

“Home is not a place but a collection of things that have fallen or been left behind.” Because of the theme of water linking these essays, I can't help imagining those things Powles mentions as the silt and dead leaves of a river bed. Is a river the geographical location where it flows, or the water that makes it up?

Rejection, Tony Tulathimutte (2024)

I listened to this audiobook in one bleary, manic Saturday. For the entirety of its daylight hours, I was alone; I alternated between obsessively charting elements of a Debussy score for my dissertation and listening to this book, and I went briefly insane. That evening I went to a small birthday party in Harlem, feeling feral. It began to snow. I finished the book on my way back home, blurry and happy.

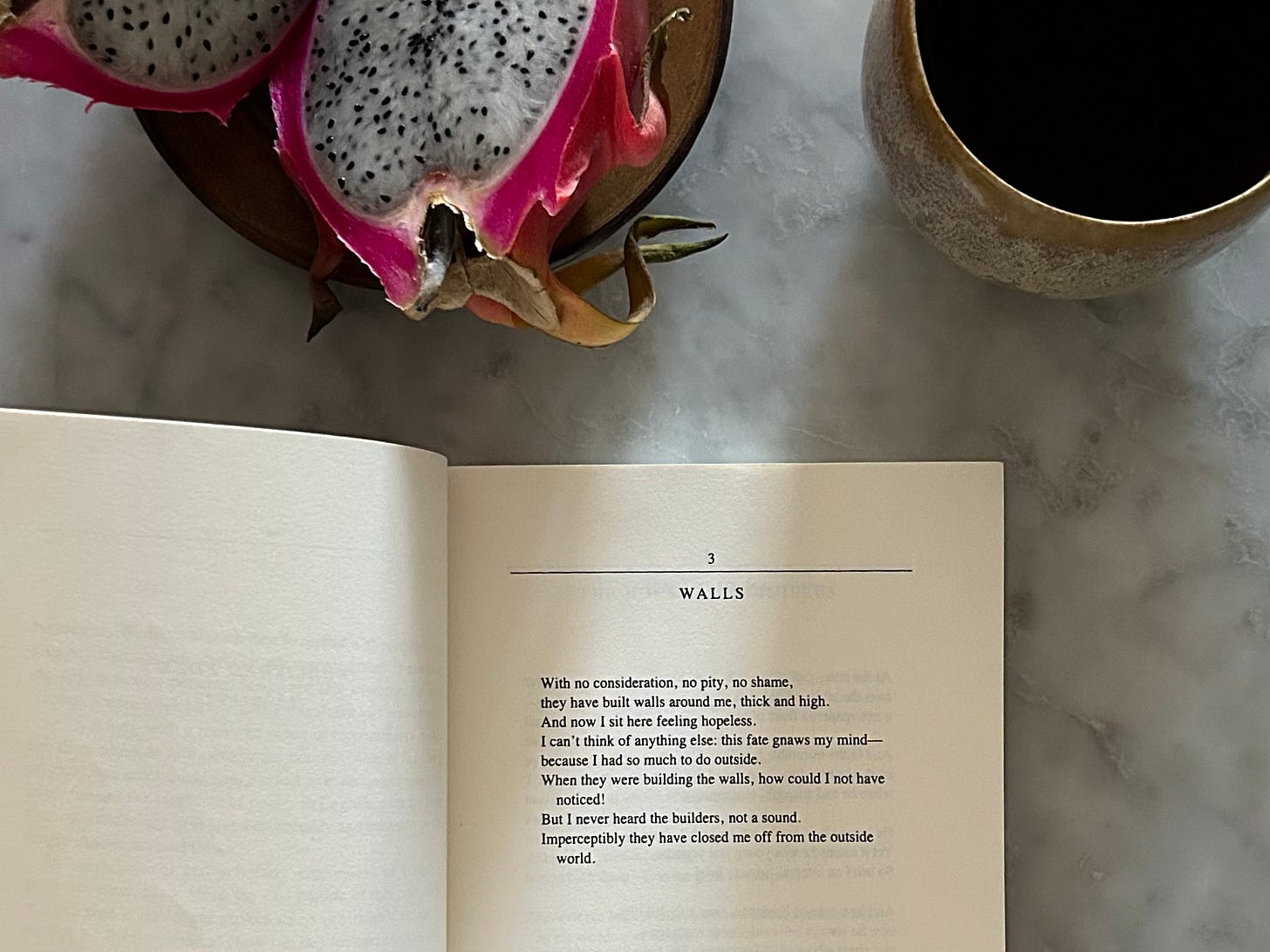

C. P. Cavafy: Collected Poems (trans. from Greek by Edmund Keeley & Philip Sherrard)

The second book I started this year, two days after coming home from my last round of chemo in hospital. On the morning of 3 January, recovering from the hospitalization and trying to grapple with the fact that treatment was not going as it should, that the American government would soon turn over, that I was starting a new year feeling particularly low, I copied “Walls” in my journal:

With no consideration, no pity, no shame, they have built walls around me, thick and high.

And now I sit here feeling hopeless.

I can't think of anything else: this fate gnaws my mind— because I had so much to do outside.

When they were building the walls, how could I not have noticed!

But I never heard the builders, not a sound.

Imperceptibly they have closed me off from the outside world.

The House of Mirth, Edith Wharton (1905)

The book that accompanied me on mid-February subway trips and walks in the park trying to feel a sense of belonging. As such, a deeply February book to me, of some loss and creeping stagnation. A book I had a difficult time with for two opposing reasons: When I could read it at a remove, it felt too long, and when I could become involved in it, I didn't want to witness the slow, impending catastrophe of Lily Bart. Who knew the House would not be so mirthful after all? (Everyone.)

Then, a series of “sickness books.”

Bibliophobia: A Memoir, Sarah Chihaya (2025)

I started the first essay of this collection in a hospital gown, waiting to have a CT scan in November, two months into chemotherapy. I was crying because things were slightly delayed, and waiting in a hospital, again, had become a trigger point of helplessness. I couldn’t wait in that state while reading Chihaya’s depression, and I had to put away the book until this month. It was illness wrapped in reading and writing, reading and writing as companion — and accomplice — to illness, that stuck to me the most. I read much of the book, finally, after several more false starts, very quickly, in my current erratically productive phase of dissertation writing and trying to taste as much life as possible.

… as I worked endlessly on my ill-fated academic book, I began to feel like I was bloating, swelling grossly like a sausage in a hot pan, my thoughts proliferating too fast for my body to contain them. There were too many ideas to write out, and I never had enough interior space for each of them to fully unfold. They just collected and built up, so that my entire body felt full of them, tight and painful.

Love’s Work, Gillian Rose (1995)

Reading this book – also slowly and then all at once – one Sunday morning drove me to write about my own representation of my illness and of myself, ill. I'm continuing to amass a reading list, not so much of pathology but pathography. “However satisfying writing is — that mix of discipline and miracle, which leaves you control, even when what appears on the page has emerged from regions beyond your control — it is a very poor substitute indeed for the joy and the agony of loving.”

The Collected Schizophrenias, Esmé Weijun Wang (2019)

Wang’s book belongs to the web of references in Bibliophobia. I'm interested in the illness memoir that isn’t about overcoming, about battling towards a definite victory. I'm interested in complicated pathography and so, by and large, I'm not interested in “fuck cancer” rah rah literature. I'm drawn more to the literature of disability, care, anger, community (e.g. Audre Lorde, Anne Boyer) and stigmatized disorder.

How to Tell When We Will Die: On Pain, Disability, and Doom, Johanna Hedva (2024)

In process as of this writing. I've been drawn to and a bit afraid of this book since it was first published, perhaps (definitely) because I'm afraid of disability and of Hedva’s brand of cool. Perhaps (definitely) because I’m in the physical/social orbit of both. I'm by turns mesmerized and ambivalent.

“I write to find out what is possible to think, meaning it's the changing of the thought that I chase, that miraculous capacity that can expand. Once I have a phrase, a sentence, a paragraph down on the page, what thrills me is to watch what happens to the thought if it's written in questions versus statements, this word rather than that word, a different syntax, vocabulary, punctuation. I want to know what thinking can do — what it makes, destroys, negotiates, protects, transgresses against; how it can be knife, fist, kiss, well, map, key.”

The Complete Saki

A very dear friend read me three Reginald — one of Saki/Hector Hugh Munro’s recurring characters — stories as I lay, both arms extended and immobile, for five hours of leukapheresis. I was uncomfortable and tired and found the short stories on the border of boringly silly. Only my love for her and my immense gratitude at having her made me cherish them.

Nasreen Mohamedi: Waiting Is a Part of Intense Living, Roobina Karode et al. (2015)

I’ve been thinking and writing a great deal about waiting, and so the title of this retrospective of Mohamedi’s work, which I didn’t notice until I began reading the first essay contained within, struck me as a lovely bit of synchronicity — a topic brought up to me by friend a few days prior. “Waiting is a part of intense living” comes from a diary entry by Mohamedi dated 12 March 1971. I wonder if synchronicity is perhaps simply an inability to leave yourself behind.

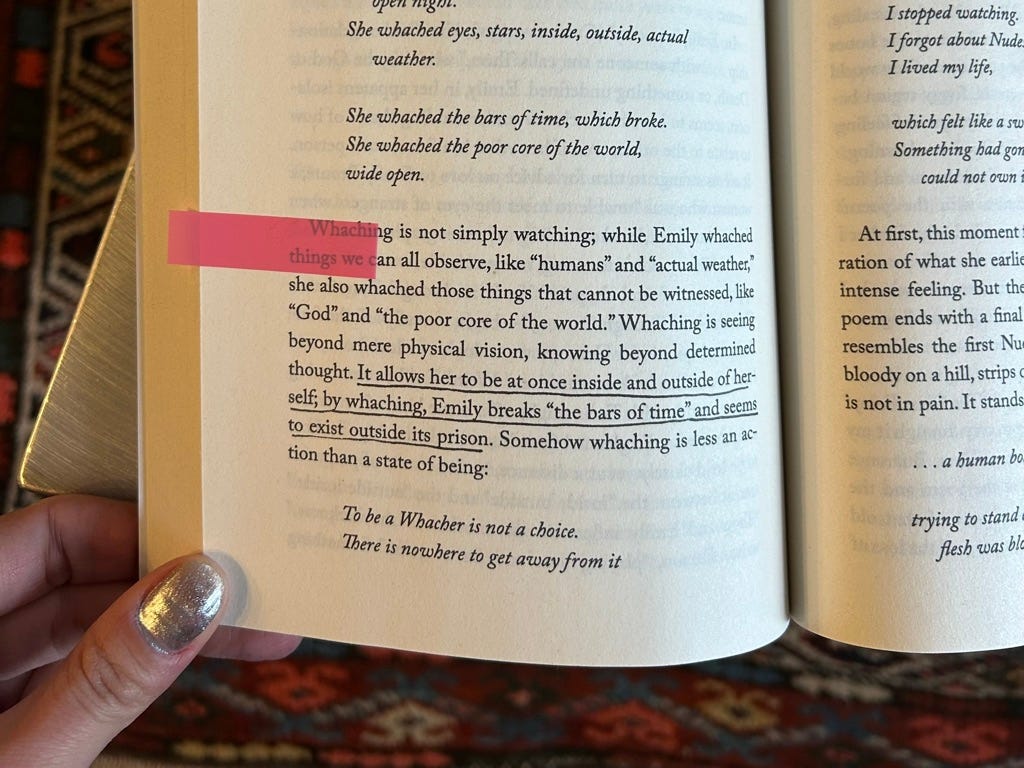

Roobina Karode on Mohamedi’s method: “Drawing was not simply a craft; it was about ‘learning to see.’ drawing was not about composing views of nature as landscapes; it was about arriving at a cosmic awareness of reality with a full consciousness of each moment in it.” And this is what writing is, too. The long, obsessive daily writing of practice pages I do is something akin to Mohamedi’s lines, repetition distilling and forming. Drawing the world on my own grid so that I force myself to see it. I'm thinking a lot about looking into and outward — this is not by any means a new concern of mine, nor is the feeling that to look at microscopic elements also results in a sudden explosion out into the beyond… Beyond self. Beyond the line of text I am meticulously interpreting. It feels like there's an actual flip in the task, a physical flip in or after the precipice of scrutiny. I bore in in in in in… and hop! suddenly I fan out. I think this is the cosmic revelation, this little massive pop, when you've gotten so granular that suddenly you're a beach again.

I suppose it's in reaching specificity that you can see that same specificity in other objects, because the thing is broken down to its component parts, parts so small that they become malleable. Perhaps synchronicity is also recognizing the atomic liaisons between moments and things. Yes, moments, because they have their own material makeup, and to drill into time obsessively is to approach “now.” Synchronicity after all deals with time, inherently, etymologically. To dig into kronos is to thread out the possibility of synchronizing, of aligning. It's what we do when we rehearse — aligning pitch vibration, physical processes and, of course, time, as beats and breaths. Mohamedi’s line drawings from the 1970s obsessively synchronized lines in parallel, as closely as possible, requiring a synchronizing of hands, of breath in the artist (a synchrony that deteriorated over the course of her life as a result of a neurological condition). And the drawings are also about moments of disharmony, lines fanning out from one another at meticulous angles. “Thin threads into space… A pure vision of nonphysical space” (diary entry, 1 September 1972).

Lote, Shola von Reinhold (2020)

I read this novel in 2021 and loved it. I read it again last week and loved it again. An archive mystery, a parody of academia and art curation, a probe into cultural establishment and erasure, a love letter to Blackness, queerness, extravagance and beauty. Just as it did four years ago, it made me want to read, research, collect and create.

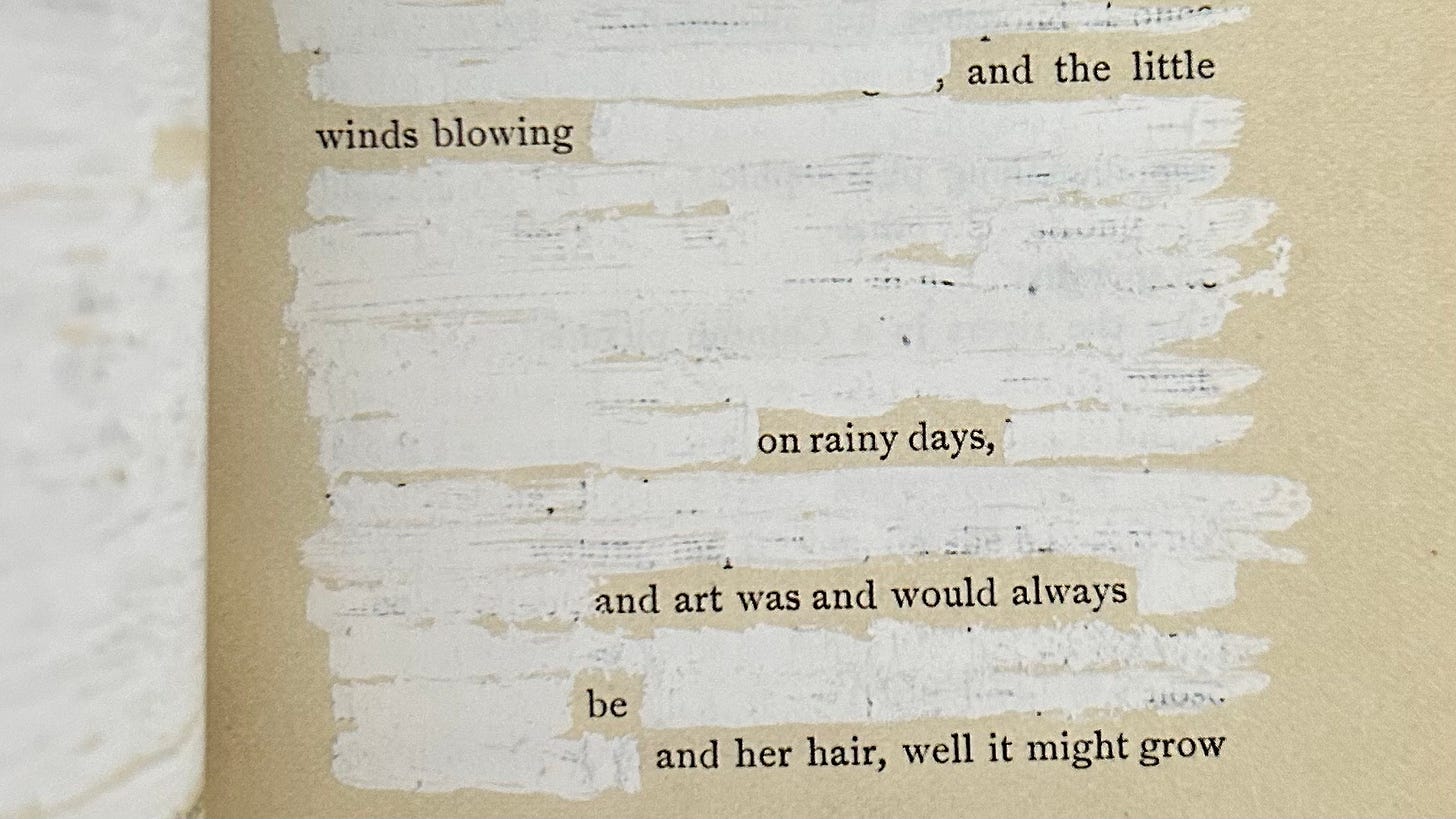

A Little White Shadow, Mary Ruefle (2006)

A tiny book (42 small pages, with very few words on each page) of blackout (or rather, whiteout) poetry, this one accompanied me on a subway ride to the Morgan Library recently. A wonderful little morsel that’s made me want to read more Mary Ruefle recommended to me: Most of It (2008); Madness, Rack, and Honey (2012); My Private Property (2016); On Imagination (2017).

In Repetition (1843), Søren Kierkegaard writes: "Repetition and recollection are the same movement, just in opposite directions, because what is recollected has already been and is thus repeated backwards, whereas genuine repetition is recollected forwards." I can’t help feeling that Aliss at the Fire by Jon Fosse (trans. from Norwegian by Damion Searls) (2003) and On the Calculation of Volume (I) by Solvej Balle (trans. from Danish Barbara J. Haveland) (2020), both of which I read in the last few days of February, each tackle repetition and recollection, and the weird space/time in which these are opposite and the same.

“…he walks into the hall and the old walls there settle into place all around him and say something to him, the same way they always have, he thinks, it's always like that, whether he notices it and thinks about it or not the walls are there, and it is as if silent voices are speaking from them, as if a big tongue is there in the walls and this tongue is saying something that can never be said with words, he knows it, he thinks, and what it's saying is something behind the words that are usually said, something in the wall's tongue, he thinks, and he stands there and looks at the walls, no, what is wrong with him today?” (Fosse)

Corps et biens, Robert Desnos

Much as I did with Cavafy last month, I’m currently making my way meanderingly through this surrealist poetry collection, letting the sounds and images set something off in me.

I appreciate you, Sophie. 🤍 Thank you as always for generously sharing your reading & thoughts with us.

Have you read Illness as a Metaphor by Sontag?